We revere Robert Louis Stevenson for his adventure novels, but he was not a genre writer in the modern sense of that term. While Black Arrow, Kidnapped, The Master of Ballantrae, and Treasure Island may seem like straightforward romantic picaresque yarns, Stevenson was always deeply concerned with the moral aspects of his story. Among his fiction, the famous novella, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde most vividly reveals his other side. The story deals with Stevenson’s understanding of the subconscious mind and the idea that good and evil can reside in the same person. Issues of morality so vexed Stevenson that he called ethics his “veiled mistress.”

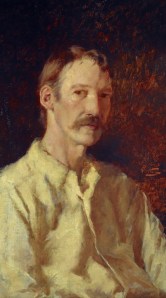

Questions of morality so concerned Stevenson that he called ethics his “veiled mistress.” All of his works carry his moral values. (Image: Wikimedia)

He may have acquired a theoretical concern with morality from his fiercely Calvinist nanny, but ethical concerns literally overwhelmed him when his artistic ambitions prompted a serious clash with his conventional and practical father. Unable to sway his obstinate parent, Stevenson had to justify to himself his decision to pursue art rather than a more realistic means of earning a living.

Stevenson came from a line of industrious and, indeed, illustrious lighthouse engineers. As is so often the case when a family prospers, an interest in art and culture began to creep in. Stevenson lived a life of privileged ease and had plenty of time to find more congenial pursuits than surveying the rugged windswept coasts of Scotland’s more remote regions. In The Wreckers, Stevenson puts his own youthful situation into the mouth of his character, Loudon Dodd:

“Unluckily, I never cared a cent for anything but art, and never shall. My idea of man’s chief end was to enrich the world with things of beauty, and have a fairly good time myself while doing so. I do not think I mentioned that second part, which is the only one I have managed to carry out; but my father … branded the whole affair as self-indulgence.”

Elsewhere in the tale, Dodd reaffirms his notion of himself: “I was born an artist; I never took an interest in anything but art.” This is certainly how Stevenson saw himself. Perhaps we should not be surprised, therefore, that he died childless.

He was, however, realistic about the price artists must pay for turning their backs on reliable sources of income while laying their precious work before the public and the critics. “In art you must give your skin.” He was against writers who “adopt this way of life with an eye set singly on the livelihood” believing that what today we would call a commercial attitude produces “a slovenly, base, untrue, and empty literature.” There could be no sacrificing of quality and depth to Mammon.

Stevenson’s vision of the artist had a decidedly elevated aspect. He believed the writer had a special role to play in society. “Designedly or not, he has so far set himself up for a leader of the minds of men ….” Since he was a role model, an influencer and opinion-maker, morality must matter to the writer. Stevenson lived by his own code. He was always a decent and responsible man even though walking this path often cost him dearly.

The artistic temperament was strong in Stevenson, yet he still possessed the trait of industriousness so evident in his Scottish forbears. He writes of “… that glimmer of faith (or hope) which one learns at this trade, that somehow and some time, by perpetual staring and glowering and rewriting, order will emerge.” Dedication is important, “for the artist works entirely upon honour. The public knows little or nothing of those merits in the quest of which you are condemned to spend the bulk of your endeavours.” Discipline must also be cultivated. “And so, in his example of unflinching industry, there lies the true moral for the aspirant. Here is the true lesson to the young gentleman who proposes to embrace the career of art.”

Stevenson spent his last years living on the island of Upolu, in Samoa, where his concern for the natives made him something of a chief among them. Although not ordained, he considered it his duty to improve the local morals by preaching the occasional Christian sermon. He is buried atop a hill above the village of Apia. The epitaph on his tomb is one of his own poems, chosen by him for the purpose.

Requiem

Under the wide and starry sky,

R. L. Stevenson

Dig the grave and let me lie.

Glad did I live and gladly die,

And I laid me down with a will.

This be the verse you grave for me:

Here he lies where he longed to be;

Home is the sailor, home from the sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.

Robert Louis Stevenson is a great writer who’s works I grew up reading over and over again!

Stevenson was a youthful favourite of mine as well. I still remember the thrill of reading Kidnapped, The Black Arrow, and Treasure Island. These books shaped my way of looking at the world.

Now when I think about it, Treasure Island may have been the first book I read.

I came across this post because I am trying to get a handle on Stevenson’s ethics at the moment. In ‘Lay Morals’ (1879) he tried to bring many of his ideas together: what is the good life, and how should we decide on conduct in the absence of a revealed morality. The good life was first of all not the conventional life of the Edinburgh middle class, pretending to govern conduct by biblical precepts and explaining by meaningless ‘catchphrases’, while actually guided by respectability and personal interest. It was more like that of the bohemian artist or of Thoreau at Walden (a major influence). And a guide to conduct came from an inner sense of what is right (another influence of American Transcendentalists), combined with ‘sympathy’ (an influence of the Scottish Enlightenment), an understanding of the feelings of other people. ‘Sympathy’ was also important in understanding the spirit of precepts. This because moral precepts can never fit the varied cases of real life and because we have to make decisions as swift as those taken on a battlefield—so we have to have internalized the spirit of any teaching.

Many thanks for the insightful comment, rdury. An especially interesting take on RLS can be found in Journey to Upolu: Robert Louis Stevenson, Victorian Rebel by Edward Rice. This lavishly illustrated little book puts forward the idea that Stevenson was a sort of modern liberal, far ahead of his time. He certainly shared many of our contemporary attitudes towards women, race, and the treatment of aboriginal peoples. Also mirroring our own time is Stevenson’s preference for emotion and subjectivity rather than duty and objectivity.